Can AI create poetry of such quality that the reader is moved to tears? According to the reports coming from Slovakia – it can! Výsledky vzniku (eng. Test of origin ) is a book of poetry by Liza Gennart, an artificial, intelligent, and quite talented author whose national poetic debut was curated by her artistic “parents” – poet and media artist Zuzana Husárová and programmer and media artist Ľubomír Panák. Their GPT-2 project convincingly suggest new directions for poetry generators, away from the production of “variable outcomes” as the value in itself, towards more emotive strategies and a better connection with the audience.

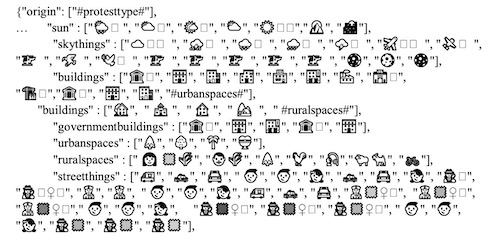

Liza Gennart is a personification of natural language processing methods and new generation of predictive text technologies represented by Open AI’s generative pre-trained transformer (GPT) models. In case of Výsledky vzniku the language model is build with GPT-2, trained on contemporary Slovak poetry and on a vast corpora of Slovak sources from the Web. The result of such AI training is the published collection of poems about humanity, maternity, nature and technology

Named by combining initials of artists’ names and the concatenation of words “generative art” Liza Gennart is a fictional entity, yet her language is not entirely artificial. It is a composite of verse and prose that the model was trained on. As such, any word that she utters can come from any other Slovak poet or user of Slovak language who left her/his linguistic trace online. In one of the poems, titled I’m not a robot, Lisa Gennart reflects on her own ontological status:

I’m not a robot

I am not a robot and I am not a woman and I am not an angel and I am not

grateful and quite silent, as my parents did.

I create my ways in my memory – my own beings, my gender.

If I had free space, I would like to be authentic, because I will never meet.

You can imagine it beyond what you like, but for the fact that it is so that it cannot be used with the disease …

Maybe that’s why you would still like to be authentic, because I like beings, and the next day I choose before it’s me. Title In mimosas the wind is too asymmetrical.

If I want to explain all these moments, I like everything in my memory.

One day I should like everything.

And so it actually started from the beginning, when in the middle class they offered us everything except the time when our sisters give us a great gift.

This fact fascinates me.

The fact that we are women should simply get rid of me.

By the second stanza one can start wondering if the text might not be something unnervingly different than the emancipatory, feminist, rebellious confession of a young student of Arts. Yet Liza’s monologue, although syntactically and semantically close to being torn apart, leads to a somewhat coherent final line. The slightly turbulent grammatical structure sounds in line with a spirit of youthful rebellion and the poetics of a literary debut; teenage angst and impatience seem rather in place.

Husárová and Panak did not hide the fact that the text is computer generated, although they also did not emphasise it explicitly in the book’s paratexts. In a bookstore, Výsledky vzniku can pass for a standard poetry book by a debuting author. In addition, several familiarisation strategies are at play in the experiment. Firstly, the unusual publication entered standard book distribution and common rituals of publishing practices: interviews, public readings, radio broadcasts (with or without the human authors). Secondly, the linguistic corpora used as the database for machine learning results in a semantic and stylistic effect that is both traditionally “poetic” and strikingly common and contemporary. Lastly, by filtering the content for the themes of family and identity, and by framing the publication as a poetic publication within the family, Husárová and Panak made the arcane, complex and alienating process of text generation a cultural artefact close to traditional expectations of the reader and to the hearts of general reading audience, Enthusiastic reception of the book in Slovakia proves that these efforts brought results. There were reports that Liza Gennart’s poems are so good that some readers were found crying. There is no reason not to believe it. The poetic AI well deserves to have a name, a book published and artistic household of which “she” is a special member.

One can observe an interesting play of agencies in the publication of Výsledky vzniku. The poetic output comes from a space of negotiated agency distributed between neural network algorithms, the linguistic pool of national language, and an artistic curatorship of Husárova. Gennart is a linguistic avatar of dispersed identity whose source can be seen broadly as the Slovak national language or even the nation itself. Yet on the level of text and discourse – in self-reflective parts of the book, in publishers’s notes, in interviews with artists – Liza is presented as a “third” daughter of her parents (Husárova and Panak parent two human daughters). The contiguity relation between traditional family tropes and the model expressed in the work is established. With it, of course, comes a challenge to traditional notions of family. However, such challenge is successfully mitigated by affective modes of artistic message that the human-AI trio expresses on all stages of the project. It is a welcome departure from the traditional focus on the multiple, variable outcome as a value in itself for poetry generators.